I first learned of the concept of truth telling when Noosa film-maker Shaun Cairns and I spent a lot of time in Timor-Leste between 2017 and 2019, making a documentary called Generation 99.

The film was produced to be shown during the celebration of the 20th anniversary of the 1999 referendum which gave our war-ravaged northern neighbor its independence, and we focused on the generation of young people whose survival was made possible through embracing art and music. Much of my research for the film was done through Centro Nacional Chega, which is the country’s truth and reconciliation commission. Chega, in the language of Timor-Leste’s former colonial masters, Portugal, means stop, or enough! It implied a line in the sand – there would be no more whispering and rumours, the truth about 25 years of torture, murder and the stealing of children would be told.

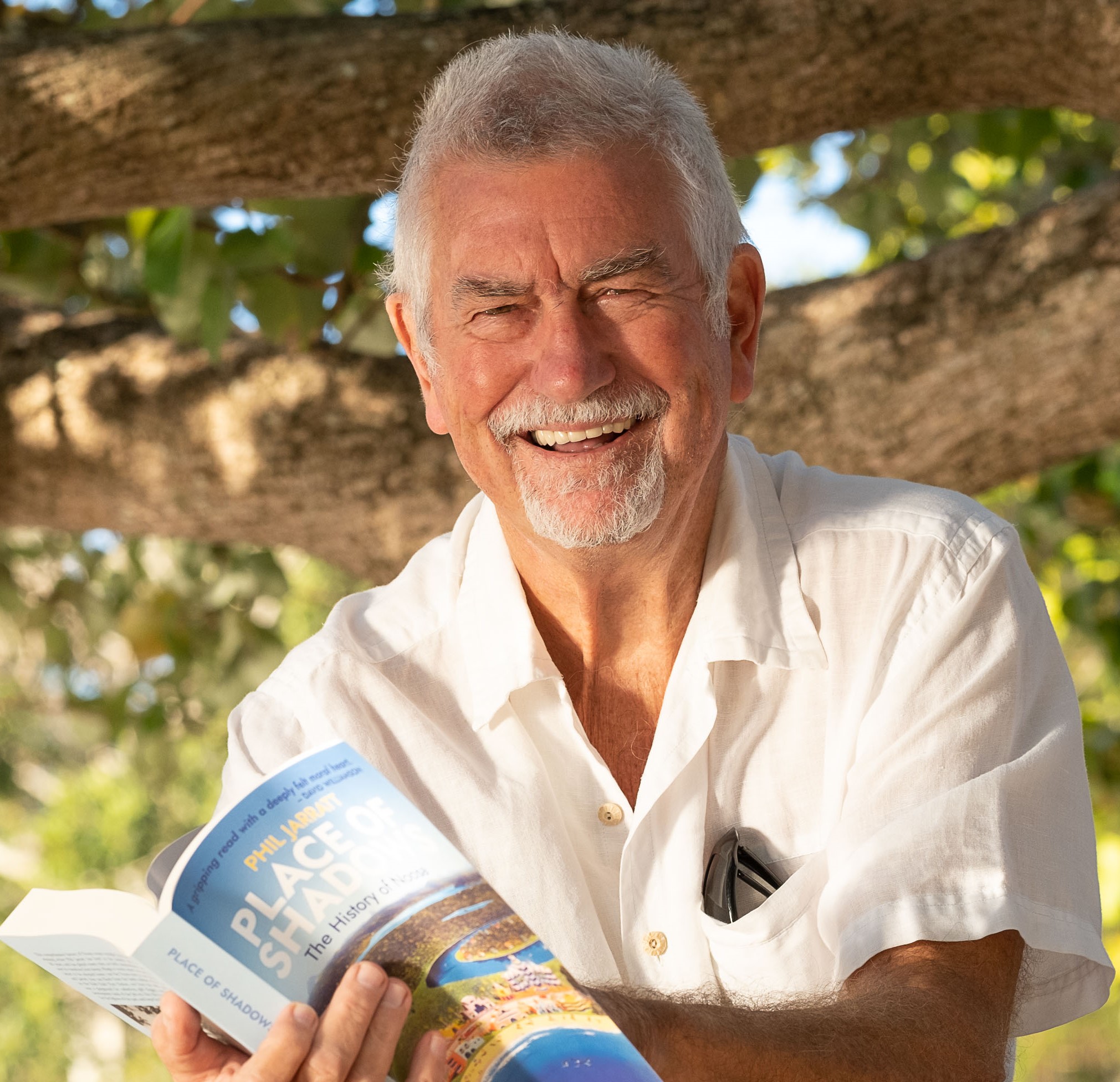

For me the takeaway from that inspiring two-year period was that we could do with more truth-telling at home, and it could start with our very chequered history in dealing with the First Nations who walked this land, cared for this country for at least 30,000 years before European settlement, possibly a lot longer. I took that sentiment with me when I began writing my history of Noosa, Place Of Shadows, in 2020, and it has been reinforced by a recent reading of Henry Reynolds’ excellent book Truth-Telling, History, Sovereignty and the Uluru Statement.

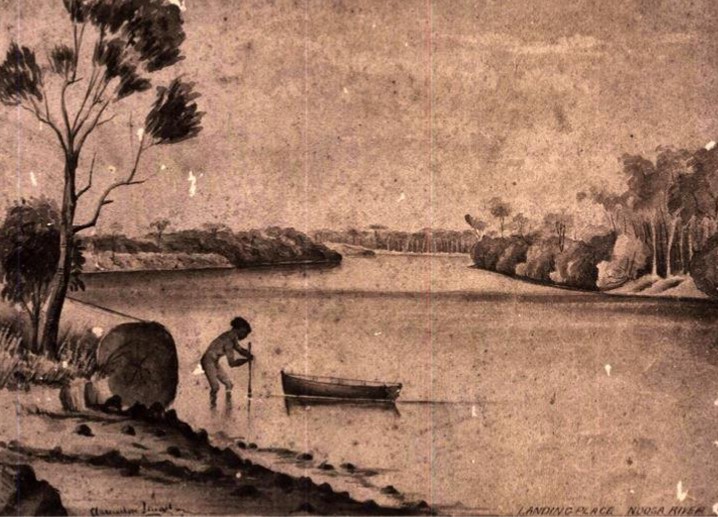

Of course, as Queenslanders, as Australians we are not alone in carrying the burden of generations of appalling injustices perpetrated against the Traditional Owners, but when you drill right down into it, as you do when writing a regional history, and look at what happened in your own backyard, it makes it very personal. It’s nearly 200 years since Europeans made contact with First Nations in what we now know as Noosa Shire, when escapees from Moreton Bay penal settlement, collectively known as the “wild white men”, sought refuge and sustenance with Kabi Kabi mobs along the banks of the Noosa River and the lakes upstream. They were taken in by the elders as the ghosts of dead offspring, tribalized and treated like their own. One of them, a wee lad from Glasgow named James Davis, known to the Kabi as Durramboi, stayed with them for 14 years.

Clearly there was a way to build relations with the Traditional Owners and it wasn’t just desperate convicts on the lam who found it. Another Scot, the builder and architect Andrew Petrie, arrived at Moreton Bay in 1840 to turn a row of cells and stockades into a city, but spent every free minute he had going bush and learning from the mobs he met. It was Petrie who acquainted NSW Governor George Gipps, then in charge of the colony, with the ceremonial significance of the bunya tree, which led to the Bunya Proclamation of 1842, which for the first time attempted to put the brakes on European settlers selecting sacred land.

These were promising signs for a future of shared and respectful occupation, but by the time the Queensland colony separated from NSW in 1859, the so-called “black wars” had begun and the Native Mounted Police was established to try to stem the rising tide of violence between blacks and whites – usually over tribal hunting parties wandering onto “selected” grazing land, as they had since the beginning of time – by getting young Aboriginal men to kill their own in return for food, tobacco and a shabby uniform.

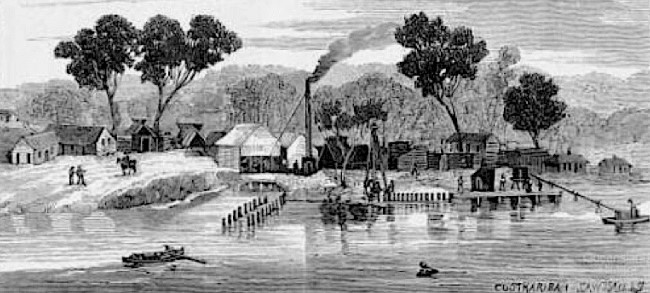

If the Murdering Creek Massacre actually happened on the southern side of Lake Weyba in the 1860s – and the Queensland Anti-Discrimination Commission in 2017 said it couldn’t find enough evidence to say it did – then that is how it went down. A troop of trigger-happy Native Police egged on by their white commander and irate local station managers. And we know for sure that this is what happened when a detachment from Wide Bay Native Mounted Police crossed Lake Cootharaba on a retaliatory mission and murdered a large group of Kabi Kabi while they gathered pippies on Teewah Beach.

(Interestingly, a recent University of Newcastle study, Colonial Frontier Massacres 1788-1930, claims that the Murdering Creek massacre did happen, between 1 February and 30 April 1862, and even names the key perpetrators. While the eight-year study claims to be the “first sustained effort to break the code of silence”, it cites its lone source on Murdering Creek as Ray Gibbons’ 2015 paper Deconstructing the Myth of Murdering Creek, the same source the Anti-Discrimination Commission rejected as hearsay. So, while the context of the black wars tells us that it certainly could have happened, we are no closer to the truth.)

As the Noosa River settlements became villages, the Kabi Kabi, deprived of their traditional hunting grounds, made camps on the edge of town and performed odd jobs for basic rations that included tobacco and sometimes rum. The elders were given brass nameplates in a gesture that hovered somewhere between respect and ridicule. The men got drunk by the campfire while their women were assaulted and raped by timber-getters from upriver and miners from Gympie. The Gympie Times moralized about it but the police did nothing.

Then, in 1897, the Queensland colonial government, in its wisdom, appointed a carnival huckster and shyster named Archibald Meston as Protector of Aborigines – despite his long history of exploiting them for commercial gain – and passed the legislation he had designed, knows as the Aboriginals Protection Act and Restriction of the Sale of Opium Act of 1897. This was the device he used to accelerate the process of forcing First Nations people off country and onto church-run mission camps.

This was when our disgraceful treatment of the Kabi Kabi became official policy. This was when more than a century of exclusion from their country, Noosa, began. And it has only been in the last quarter century since the Mabo judgement, that we’ve started to do something about it. And only in the last decade that we’re starting to see results, with young people slowly coming back on country and taking jobs in land care, tourism and other areas where their spiritual affinity with the land can be nurtured.

In recent years I’ve learnt a lot about the Kabi Kabi from the work of academics like Dr Ray Kerkhove, historian in residence at Noosa Library in 2020, and from the century-old contributions of the Reverend John Mathew and linguist Fred Watson, both of whom lived with the Kabi Kabi on country in the 19th century and saw them living in penury at Cherbourg Mission in the 20th century. Rev Mathew was also pretty good on the myths and stories that he heard as a boy, and today the oral tradition continues with people like Kabi man Lyndon Davis and others.

What I haven’t read or heard enough about is the interaction between black and white, other than race-tinged pub yarns from the likes of author DW Bull. We learn a little about it from James Muller’s moving 2019 documentary Place Of Crowes, and from the stories of the exiled Kabi Kabi descendants, but our settler families go back well into the 19th century and I wonder if great-grandpa’s old diaries lurking in attics and basements might reveal something about the realities of relations between settlers and First Nations.

Maybe there are as many good stories as there are bad. Maybe it’s time for some truth-telling in our own community.

This article is adapted from an address given by the author to the Noosa Parks Association Friday Environmental Forum on 25 February.